The Art of PTSD

A Review of Art Therapy as a Treatment for Combat-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Author’s Note

Courtney Banzon is a fourth year undergraduate student studying Psychology and Sociology at the University of California, Davis. Courtney’s interests in psychology lay primarily in the realm of clinical and abnormal psychology. Through her studies, Courtney learned about the use of exposure therapy to treat combat veterans with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This piqued her curiosity about other methods used to treat trauma disorders. This curiosity, paired with her love of the arts, motivated her to conduct a literature review examining the efficacy of art therapy for treating PTSD in combat veterans. Through this review, she hopes to highlight the value of integrating science and art to create innovative new treatments for psychological disorders that are more effective, cost-efficient, and enjoyable than previous methods.

Introduction

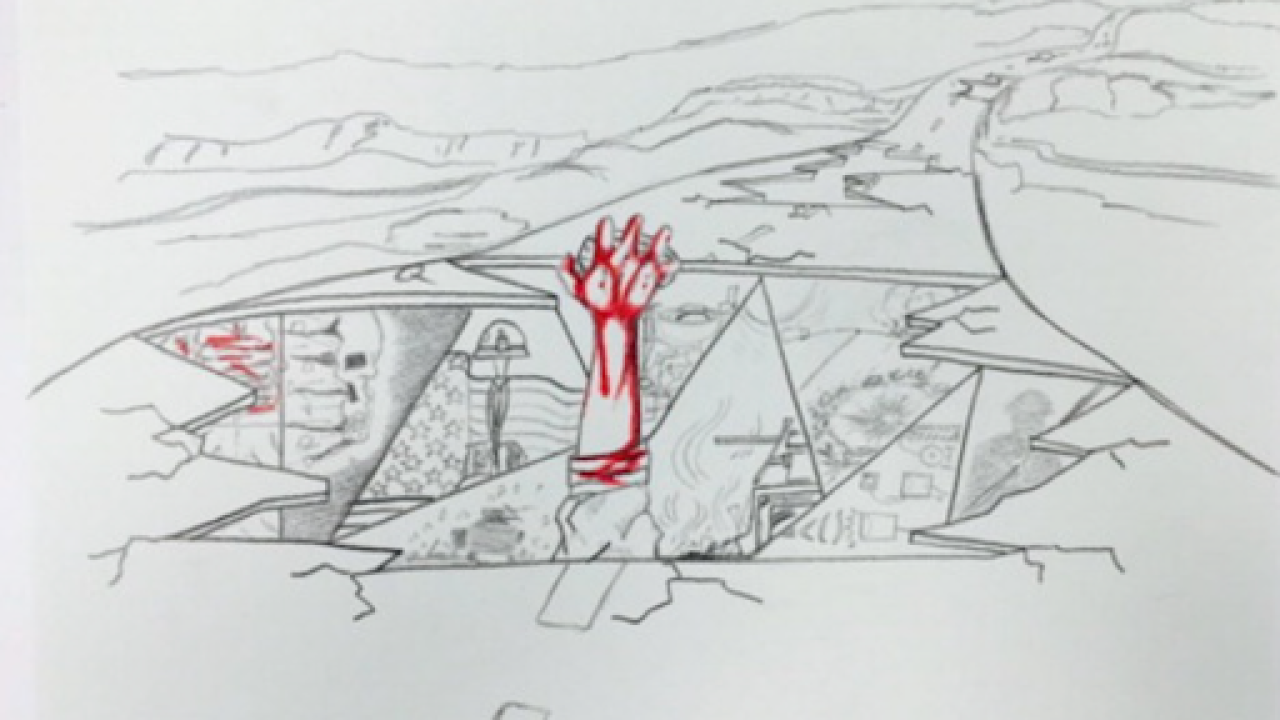

Millions of American soldiers have died at the hands of war. Those who survive return home with their lives, but are often plagued with memories of war for the rest of their lives. Historically, these individuals have been diagnosed with “battle fatigue,” “shell shock,” and “soldier’s heart.” Today we refer to it as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD can arise from any source of trauma, but combat-related PTSD among war veterans is one of the most common forms. PTSD is difficult to treat; studies have shown combat-related PTSD to be resistant to improvement by typical talk therapies, perhaps due to some impairment of verbal memory. Other forms of treatment, including more visually expressive methods such as art therapy, may achieve better results.

This literature review synthesizes five independent studies that examine the efficacy of art therapy as a form of treatment for combat-related PTSD. Four of the five studies (Campbell et al., 2016; Decker et al., 2018; Jones et al., 2018; Morgan & Johnson, 1995) are experimental research studies, while the fifth (Spiegel et al., 2006) is a literature review. Most of the experimental studies compared art therapy to only one alternative form of treatment (Campbell et al., 2016; Decker et al., 2018; Morgan & Johnson, 1995). Jones et al. (2018), however, compared art therapy to over three dozen alternative treatments. The paper by Spiegel et al. (2006) combined data from interviews with art therapists and psychiatrists with a literature review in order to make recommendations regarding the “best practices” for the future research and practice of art therapy as a treatment for combat-related PTSD. These “best practices” utilize the unique characteristics of art therapy (including non-verbal and symbolic expression, containment of traumatic emotions within an object or image, and the pleasure of artistic creation) to reduce individuals’ immediate PTSD symptoms and address the underlying causes and traumas that contribute to the disorder.

In general, all the research studies found that art therapy was an effective and well-liked form of treatment for combat-related PTSD. They suggest that art therapy, either on its own or combined with other forms of treatment, can be an effective tool to alleviate the symptoms of war trauma.

Consistency of Therapeutic Mechanisms

Compared to more well-established treatments like cognitive behavioral therapy, art therapy has a huge variety of potential goals and techniques. Luckily, all four of the experimental research studies are relatively consistent with both their goals and techniques. This may be due to the influence of the review conducted by Spiegel et al. (2006), considering the high degree of lexical similarity between this paper’s recommended “best practices” and the therapeutic mechanisms instated by Campbell et al. (2016), Decker et al. (2018), and Jones et al. (2018). Morgan and Johnson’s (1995) study is the exception, likely because their work was conducted prior to the publication of Spiegel et al. (2006).

The efficacy of the techniques and activities utilized in these research studies is supported by the literature on art therapy for non-combat-related trauma. The construction of a visual trauma narrative, which involves 2D artwork like drawing, painting, and collaging, is one of the most widely used forms of art therapy. Constructing a trauma narrative in a therapeutic environment is a common practice in trauma-informed care, yet it typically relies on the patient’s ability to use words to talk through or write down their trauma. Art therapy, on the other hand, seeks to avoid reliance on verbal memory. Hence, patients are instructed to visually illustrate the timeline of their trauma, including moments before and after the traumatic event during which they felt safe. This pictorial narrative allows patients to externalize memories of their trauma and safely interact with them from a third-person point of view, which aids in the reconsolidation of memories via non-verbal expression.

The visual trauma narrative also encourages progressive exposure to aversive stimuli, as do the activities of mask making, mind mapping, and montage creating. Mask making allows participants to visually represent the difference between their internal self and the version of themself that they present to others. This project encourages the incorporation of mixed media, including clay or small objects, to explore the various aspects and versions of one’s identity. Mind mapping occurs simultaneously; participants draw a “web” of lines that connect their name to individual emotions that emerge while creating the mask. The montage activity involves a combination of painting and collage, and is meant to help participants process an event from their past, their feelings at the present, or their hopes for the future.

Together, the therapeutic mechanisms of these research studies align well with the “best practices” recommended by Spiegel et al. (2006). Each study involved non-verbal activities that allowed participants to externalize and contain their emotions via symbolic expression (Campbell et al., 2016; Decker et al., 2018; Jones et al. 2018). Additionally, they fostered feelings of autonomy associated with creating one’s own artwork within a supportive group setting, which improved participants’ self-esteem, emotional self-efficacy, and experience of positive emotions (Campbell et al., 2016; Decker et al., 2018; Jones et al. 2018; Morgan & Johnson, 1995). Due to the highly similar goals and therapeutic mechanisms of these studies, their results can be closely compared.

Results

Each study measured and compared the efficacy of art therapy to at least one other form of PTSD treatment. Campbell et al. (2016) found that cognitive processing therapy (CPT), a PTSD-specific form of talk therapy that involves evaluating and changing negative thoughts about one’s trauma, combined with art therapy was more effective than CPT alone. Decker et al. (2018) replicated the Campbell et al. (2016) study a few years later and found similar results: “the experimental group improved to a statistically significantly greater degree than the control group with respect to PTSD symptoms” (Decker et al., 2018, p. 191). In other words, art therapy combined with CPT significantly reduced symptoms relating to hyperarousal, reexperiencing trauma, and avoiding aversive stimuli, though it did not significantly decrease emotional numbing. In addition to collecting quantitative data, Campbell et al. (2016) and Decker et al. (2018) measured participants’ perception of their treatment. In both studies, patients were highly satisfied with their treatment regardless of which form of therapy they had received. However, the patients who received both CPT and art therapy consistently rated art therapy as a more satisfying and beneficial form of treatment than CPT.

Similar to Campbell et al. (2016) and Decker et al. (2018), Jones et al. (2018) incorporated participant feedback into their study, though to a much greater degree. “Program evaluations” were distributed regularly over the four-week treatment period as a way for patients to have a voice in their own treatment plan. The art therapists adapted in response to patient feedback; they allowed patients to advocate for their own needs by involving them in discussions regarding quality of care and program development. Out of over forty different forms of therapy available through the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE) at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center where this study took place, patients ranked art therapy as one of the top five most effective forms of treatment. Over 80% of patients reported that art therapy positively impacted their ability to experience positive emotions, and over 65% reported significant decreases in their avoidance of trauma-related stimuli.

Compared to the previously mentioned studies, the experiment conducted by Morgan and Johnson (1995) was much simpler, yet published congruent results. To test the effectiveness of art therapy on veterans’ nightmares, participants were assigned to either a drawing or a writing task. Completing a drawing task immediately upon waking from a nightmare led to significantly fewer and less intense nightmares compared to completing a writing task. Participants also reported an improved ability to return to sleep after a nightmare in response to the drawing condition (Morgan & Johnson, 1995).

Discussion and Recommendations

The highly consistent results of these four research studies seem to paint a promising future for art therapy as an effective and well-liked form of treatment for combat-related PTSD. This is an exciting initial conclusion, but it is important to recognize the flaws and confounding factors present in the literature. A serious flaw in the methodology of Campbell et al. (2016), namely that the experimental group received twice as many hours of treatment as the control group, likely skewed the results. This error was recognized and corrected for in the replicated study conducted by Decker et al. (2018). A similar confounding variable may be present in Jones et al. (2018): the sheer volume of available treatments likely augmented patients’ improvement, thereby positively influencing their perception of the benefits provided solely by art therapy.

An additional limitation of these studies is their small sample size. The Morgan and Johnson (1995) study in particular had an extremely small sample consisting of only two participants. The results of this study were likely affected even further when both participants discontinued the control condition (writing task) significantly before discontinuing the experimental condition (drawing task) due to their preference for the latter. Similarly, dropout rates for the control condition were high for Campbell et al. (2016). About 40% of participants assigned to the control group (CPT only) dropped out early, which is consistent with the field’s 36% dropout rate for PTSD psychotherapies overall. By contrast, none of the participants in the experimental group (CPT and art therapy) dropped out, indicating that art therapy may encourage greater retention rates that other forms of PTSD treatment have failed to achieve.

To understand and resolve the high dropout rates associated with PTSD psychotherapy control groups, all four studies collected some degree of patient feedback. Such feedback may reveal that, for this population, the patient’s perception, or liking, of the treatment may be a greater predictor of their commitment to the treatment program than the actual efficacy of the treatment itself. Further research should be done in this area to determine the importance of patients’ perception of their treatment; if degree of liking is significantly correlated with successful treatment, then professionals and practitioners in this area of study should redesign their treatment programs to account for it.

In addition to high dropout rates, a notable limitation on the generalizability of the literature is the absence of female participants. Female veterans comprise roughly 10% of the United States’ veteran population, and that percentage is expected to grow to over 16% in the next twenty years (National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, 2017). Given the growing proportion of female combat veterans, many of whom will struggle with PTSD upon returning home, it is important that female veterans are included as participants in research studies of combat-related PTSD treatments. However, this area of research involves subject pools that are predominantly or completely male. This is not without reason, as males do comprise the majority of the veteran population, but the lack of female participants limits the generalizability of these studies. Female veterans may have unique needs or respond to treatment differently than male veterans, yet there is not enough data on the efficacy of treatment for this subpopulation to draw any conclusions.

Within the data that is currently available, limitations include the inherent issues of self-reports and, most crucially, the lack of long-term data. Participants may struggle with honesty, accurate self-assessment, question interpretation, and bias when providing self-reported data, which may decrease the accuracy of results. Furthermore, it would be helpful to analyze long-term data of each treatment’s efficacy, but none of these studies lasted more than a few months. None have conducted long-term follow up studies either, though not enough time has passed since the original date of the studies (excluding Morgan and Johnson, 1995, though a long-term follow up of this study would likely be worthless given the exceedingly small sample size) for long-term data to be available yet. That said, collecting long-term data on the effectiveness of art therapy should be the primary goal for researchers in this field since none such data currently exists.

Conclusion

The reviewed literature supports the efficacy of art therapy as a form of treatment for combat-related PTSD. All studies found that art therapy was effective at lessening PTSD symptoms and was generally preferred (by patients) over other forms of treatment. Combined, these studies have followed every recommendation set forth by Spiegel et al. (2006). Areas of symptom improvement included enhanced trauma recall, increased ability to experience positive emotions, reduced flashbacks and nightmares, reduced hyperarousal, and increased self-esteem and sense of self. Future research should focus on recruiting larger, more diverse samples, and should be designed as a long-term experimental study or include a long-term follow up. Art therapy may be the ideal PTSD treatment plan we’ve been looking for—it is a flexible, non-invasive, and non verbally-reliant form of therapy—but further research is necessary to know for certain.

Author's Bio

Courtney Banzon

Graduation: Spring 2023

B.S. Psychology

References

Campbell, M., Decker, K. P., Kruk, K., & Deaver, S. P. (2016). Art therapy and cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 33(4), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1226643

Decker, K. P., Deaver, S. P., Abbey, V., Campbell, M., & Turpin, C. (2018). Quantitatively improved treatment outcomes for combat-associated PTSD with adjunctive art therapy: Randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 35(4), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2018.1540822

Jones, J., Walker, M., Drass, J. M., & Kaimal, G. (2018). Art therapy interventions for active duty military service members with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. International Journal of Art Therapy, 23(2), 70–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1388263

Morgan, C. A., & Johnson, D. R. (1995). Use of a drawing task in the treatment of nightmares in combat-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 12(4), 244–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.1995.10759172

National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics, Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017).

Women Veterans Report: The Past, Present, and Future of Women Veterans.

https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Women_Veterans_2015_Final.pdf

Spiegel, D., Malchiodi, C., Backos, A., & Collie, K. (2006). Art therapy for combat-related PTSD: Recommendations for research and practice. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, 23(4), 157–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2006.10129335